BURAIHA: The ‘decadents’ of Japan

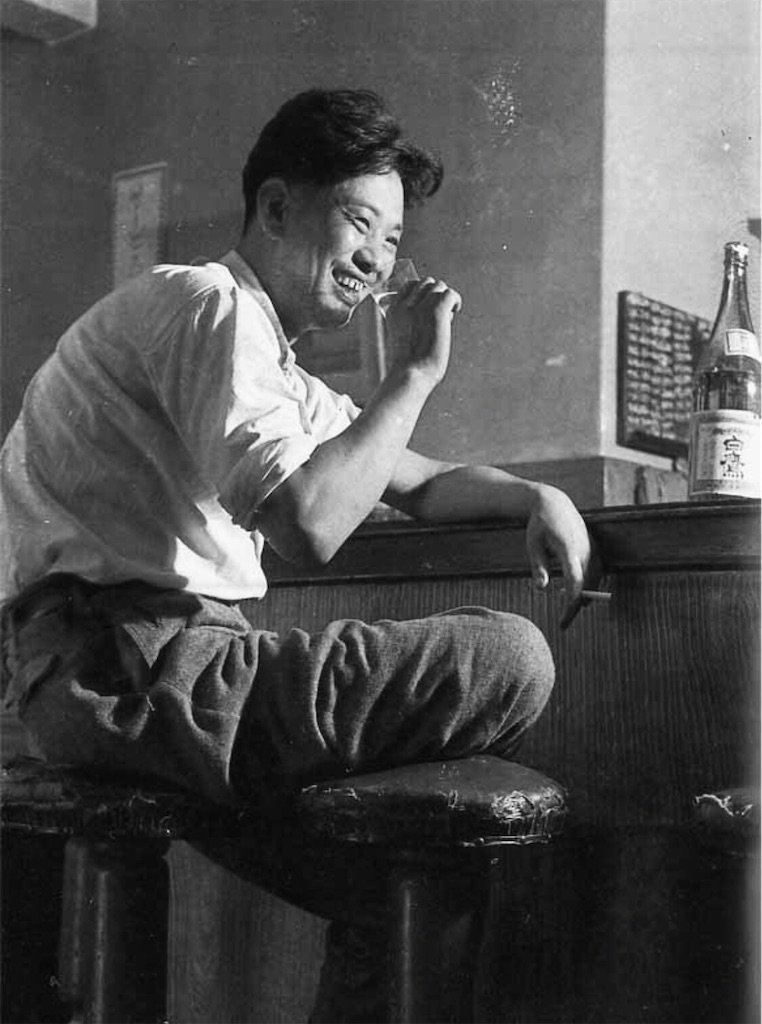

Buraiha (無頼派) was a literary group active in the post-WWII period known as the “school of irresponsibility and decadence.” Not a properly defined collective, the ragtag group of authors received the label ‘Burai’ from conservative critics. Linked by their exploration of nihilism and a lack of identity, the authors became notorious for their controversial works and bohemian lifestyles.

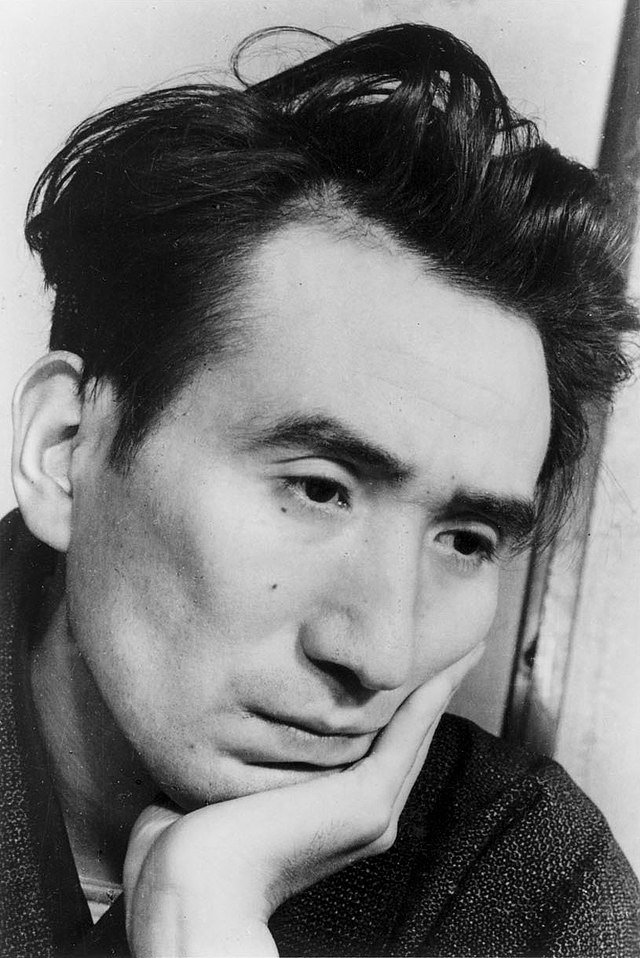

osamu dazai

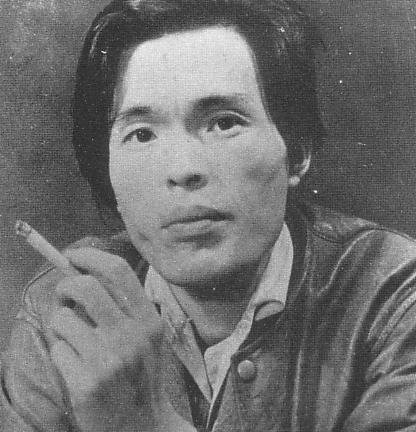

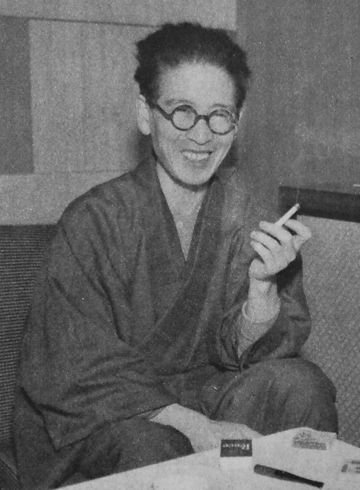

Before ‘Burai’, the author Ango Sakuguchi coined the term “Shin-Gesaku” in the late 1940s. He called for a revival of ‘Gesaku’, an Edo-era movement that rejected beauty and perfection to focus on absurd entertainment that appealed to a wide audience. With this, Sakaguchi catalyzed the Burai movement as more and more authors rejected the orthodox, elitist style of pre-war literature and joined the farcical world of Shin-Gesaku. Other notable persons during this period were Osamu Dazai and Sakunosuke Oda.

sakunosuke oda

The most prominent work to emerge from the Buraiha was Sakaguchi’s 1946 ‘Discourse on Decadence.’ In this, he condemned the notion of ‘bushido’ for justifying the Imperial war machine and claimed that humanity is doomed to fall into decadence. He posited that Japanese leaders have done so for centuries. The essay drew widespread criticism from conservatives who were trying to rebuild a national identity in the wake of their devastating wartime loss. On the other hand, it offered a highly relatable and comforting way of accepting their situation for many of the younger and more liberal residents of the country.

Many of the Buraiha authors were tragic figures engaged in frequent drinking, narcotics use and sordid sex lives that shocked established Japanese society. Notably, Osamu Dazai was a serial adulterer who ultimately drowned himself alongside his wife in the Tamagawa Aqueduct. Hidemitsu Tanaka, another Buraiha author, committed suicide in front of Dazai’s grave a year later.

While the movement was short-lived and chaotic, the Buraiha writers had a lasting impact on Japanese culture and laid the foundation for the existential and socially rebellious media/culture that would come out of the 1950s such as Taiyou-zoku & Bosozoku.