SUN TRIBE: The disillusioned youth of postwar Japan

The 1950s was a period of intense social upheaval and radical change in Japan as the country struggled with a loss of identity in the face of WWII defeat while simultaneously enjoying a new-found democratic freedom under American occupation. This struggle for self identification manifested itself most prominently in the youth of the postwar period. This phenomenon was not limited to Japan, however, with films like Rebel Without a Cause coming out of the US and Colin Wilson’s book The Outsider shedding a light on the existential nihilism coursing through the veins of the world’s youth. The older, traditional generations who had struggled through the wars were being sent into a moral panic and Japan was no different.

1956 poster for ‘Season of the Sun’ (Taiyou no Kisetsu) | source: nikkatsu

In Japan, the most notorious of these disillusioned youngsters were the children of the rich, pre-war aristocratic families who still had significant coffers of money to fund their nihilistic lifestyle. The media was so concerned with these wealthy, rebellious teenagers that a term was coined to describe them - Taiyouzoku, or the Sun Tribe. The name itself is a portmanteau taking the word taiyou (sun) to refer to their propensity to laze about on the beach and zoku (tribe), a nod to their wealthy shayo-zoku (pre-war aristocratic) parents.

kon ichikawa’s 1956 film ‘Punishment room’ (Shokei no heya) - a tale of misogny, violence and futility | source: rakuten

The feelings of this Sun Tribe first made their way into the mainstream through the literary works of Shintaro Ishihara (the same man who ended up serving as the conservative governor of Tokyo from 1999-2012). Ishihara’s first book was ‘Season of the Sun’, printed in 1956, and from there he filled the pages of several books with the fantasies of an aimless Japanese youth. His stories centered on themes of hyper sexuality, absent parents, thoughtless spending and hypermasculine violence. Before even graduating from university, Ishihara received the prestigious Akutagawa literary prize for Season of the Sun and the Taiyouzoku were simultaneously thrust into a state of both celebrity and infamy.

For the older generations of Japan, Ishihara’s writings represented a complete abandon of morals and order. On the other hand, after receiving the Akutagawa prize, Ishihara was swamped with letters from other youngsters applauding him for managing to perfectly capture their feelings and desires in the postwar society.

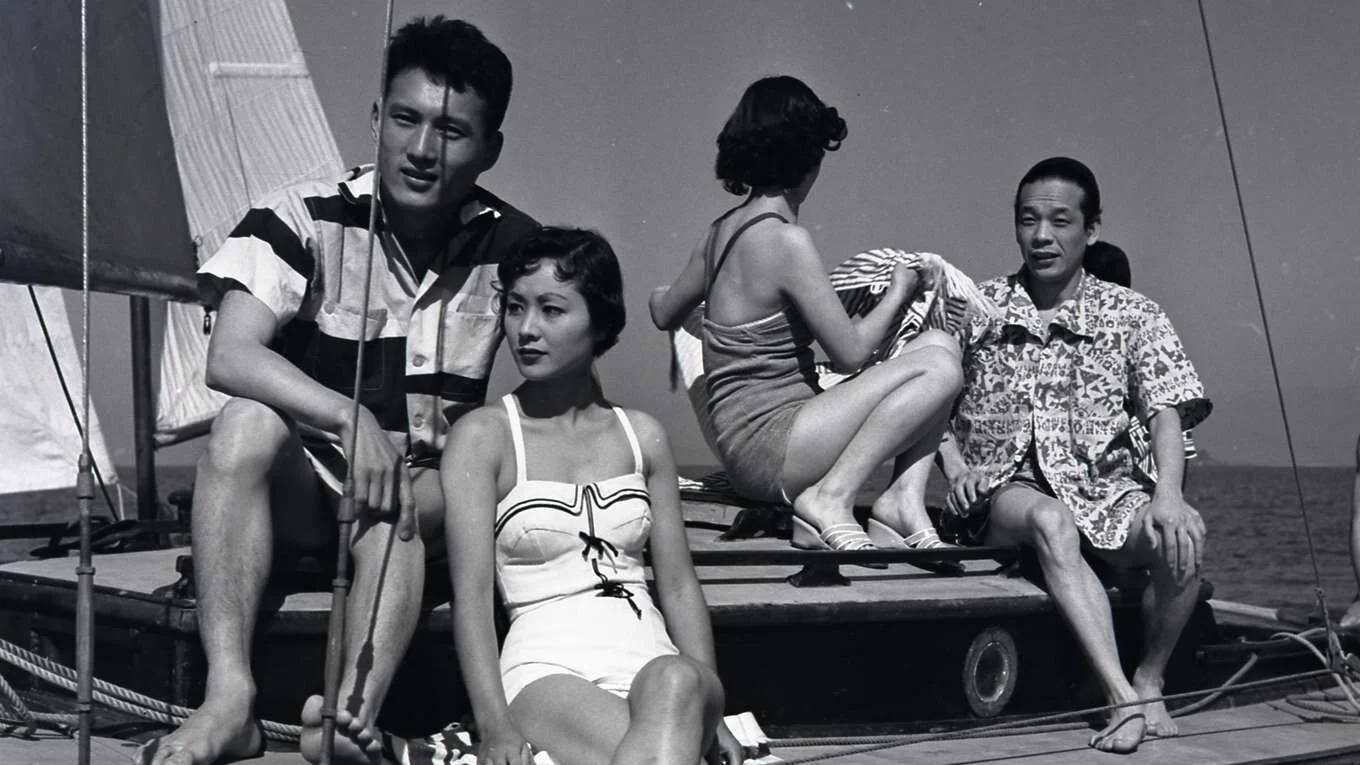

rich youngsters lounge on a boat in Season of the Sun | source: unext

Riding on the success of his novels, Ishihara looked to incorporate these stories onto the big screen. The Taiyouzoku films tended to be shot in a very short period of time (a matter of weeks) and the raw, choppy editing perfectly mirrored the shambolic nature of the youth themselves. The year 1956 saw Nikkatsu release five films, all with the involvement of Ishihara, that are considered to be the original, core Sun Tribe works. The major breakout from these films was not Shintaro though, it was his brother - Yujiro - who often played the role of the aggressive, unscrupulous and nihilistic older brother in Shintaro’s films. Yujiro’s machismo and recklessness on screen launched him into superstar status as a figure akin to James Dean for the youth of Japan. He became a conduit through which the despondent youngsters of the nation could vicariously live their newfound, anti-establishment fantasies.

yujiro ishihara & mie kitahara in Crazed Fruit (Kurutta Kajitsu) | source: joel trose

While the novels had already caused a stir, the visual medium and Yujiro’s portrayal of this anti-hero made the controversial themes of Ishihara’s work all the more offensive. The teenagers of the films were shown gallivanting about the beachside towns of Japan drinking, smoking, listening to jazz and generally rejecting all of the social norms of a conservative Japanese society. Their purposeful turn towards American consumerism was particularly insulting to many older members of Japanese society who were still processing the defeat in WWII.

More shocking to traditional audiences than anything, however, was the Sun Tribes brutal and unflinching portrayal of male sexuality. The fatalistic main characters of the films, all men, are concerned only with their own gratification. Up until this point in Japanese cinema, even the filming of a kiss was taboo, and yet the Sun Tribe presented characters spiking the drinks of their female companions and assaulting them for little more than their own momentary pleasure.

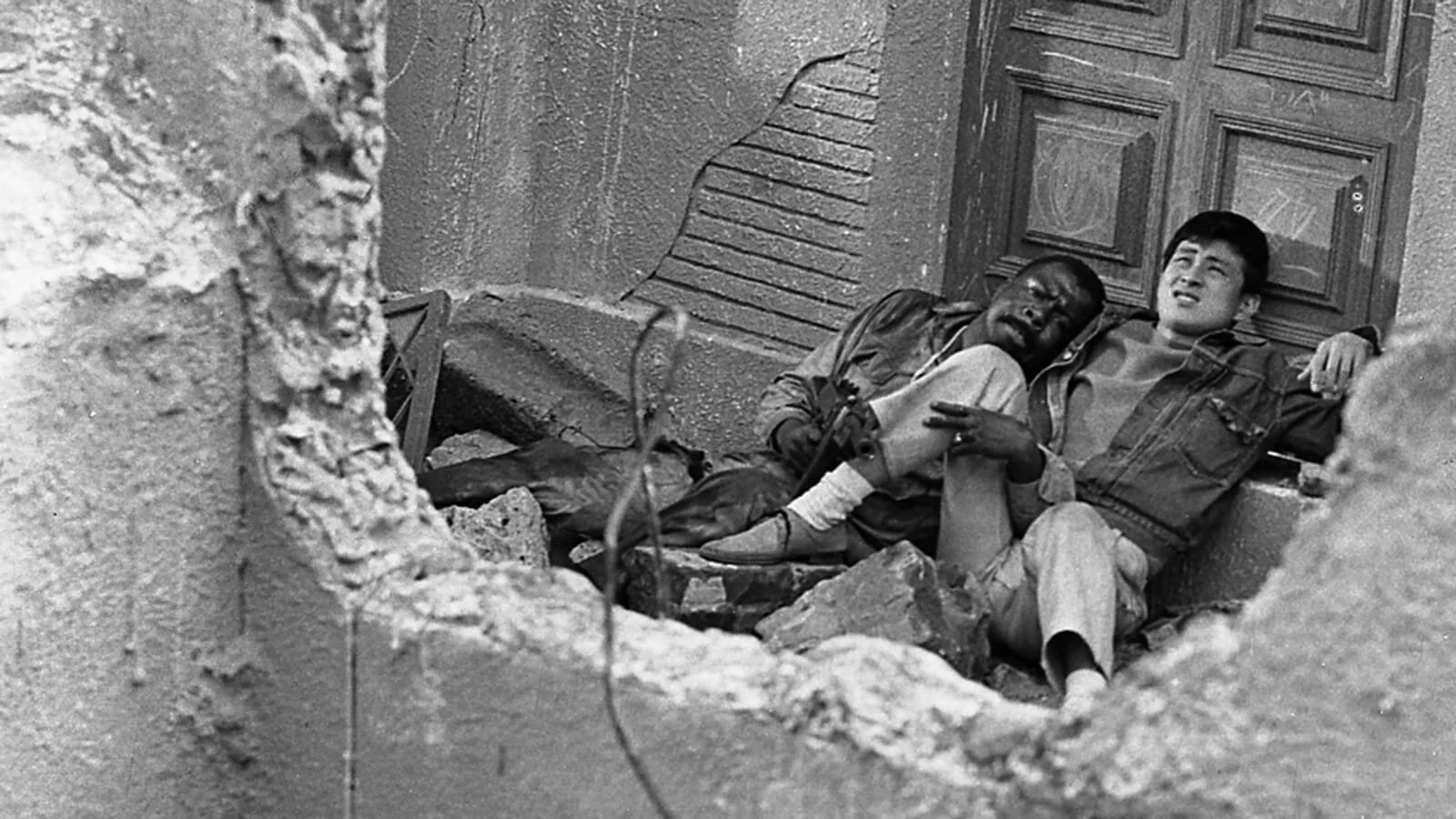

koreyoshi kurahara’s The Warped Ones (Kyōnetsu no kisetsu) - released in 1960, this film was not one of the original 5 sun tribe productions but took huge inspiration from ishihara’s works | source: festival of the 3 continents

Nikkatsu, which had been struggling to stay afloat until 1954, earned huge profits off of the scandal and hysteria surrounding the Sun Tribe films. However, the mounting social pressure eventually became too much for the studio to bear. Newspapers began to report on fears of hoodlum attacks in seaside areas and PTA groups officially protested the airing of the films. Nikkatsu bowed to this pressure and in 1956 they announced that no more Sun Tribe films would be produced, effectively ending Ishihara’s brief period at the forefront of Japanese youth culture.

While it may have only lasted a year, it became evident that the Sun Tribes initial, seminal works had led to a cultural reset. Nikkatsu’s films up until the mid 60’s, while not linked to the original Sun Tribe, covered much of the same moralistic concepts but often stayed away from the more universally shocking themes of torture and sexual assault that Ishihara had employed. Through the likes of auteurs such as Koreyoshi Kurahara, Nikkatsu continued to churn out masterpieces such as The Warped Ones, a tale of ultimately unfulfilling crime, violence & sex.

koreyoshi kurahara’s Black Sun (Kuroi Taizoku) - one of the last films released (1964) that can be fit into the Sun Tribe category | source: criterion

From the mid 1960’s onwards, Japan was no longer struggling to find its legs under the weight of American occupation. It was experiencing the start of a complete economic rebirth that would last it until the early 90s and return it to the forefront of the world stage as a major power. As life itself became more comfortable, the desire for anarchy and rebellion rapidly subsided. Nowhere was the death of the Sun Tribe more evident than in Shintaro Ishihara himself - following his career as the mouthpiece for a radical youth, he entered politics and became an increasingly conservative, misogynistic, racist and controversial figure as the Governor of Tokyo.

While the Sun Tribe works may have been grotesque in their violence and objectification of women, they captured the existential and selfish rebellion of a generation that found itself lost in a period of social transition. The central themes that the Sun Tribe were questioning are not limited to the teens of the 1950s, but represent the fundamental, animalistic and ultimately dangerous response that humans have when confronted with a loss of meaning.